Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe:

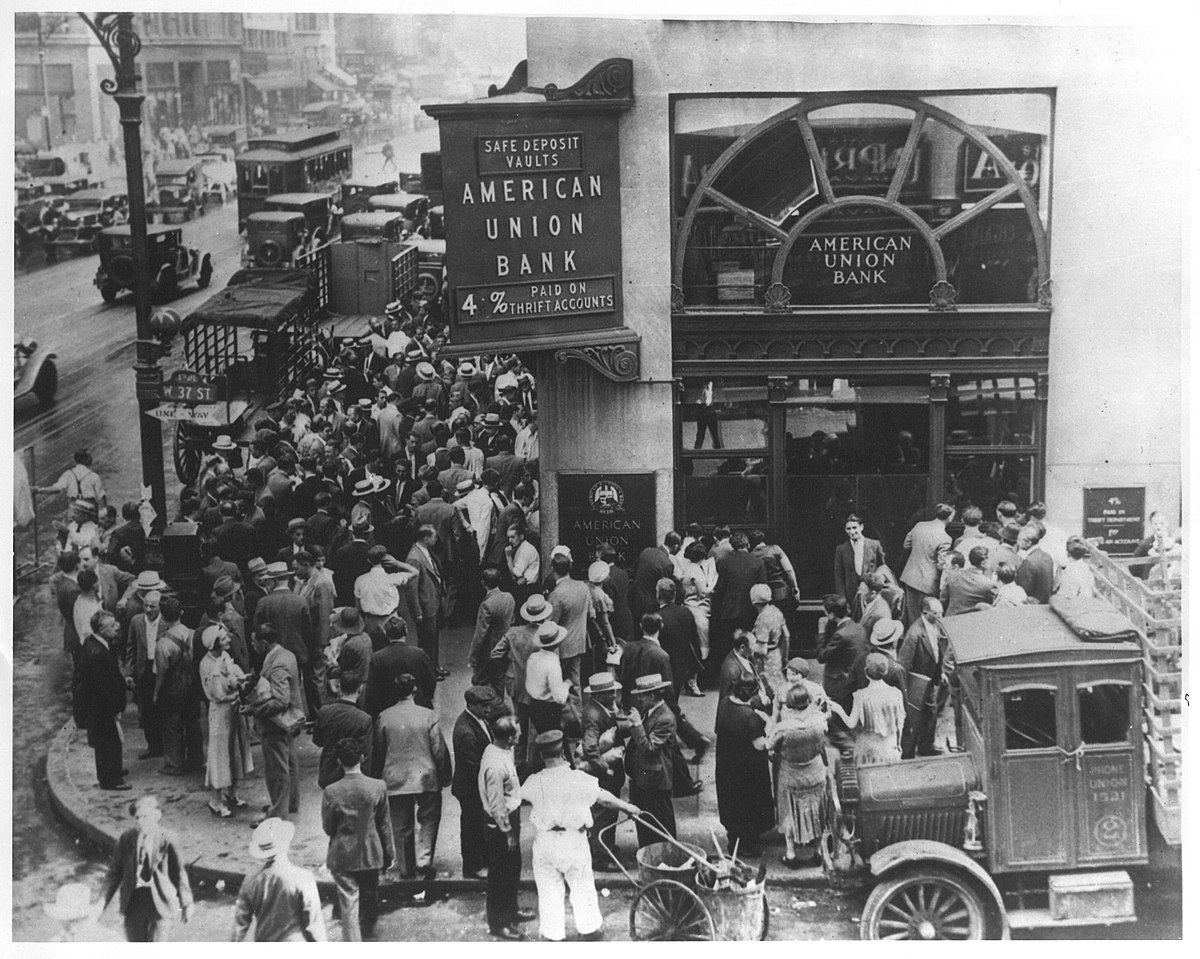

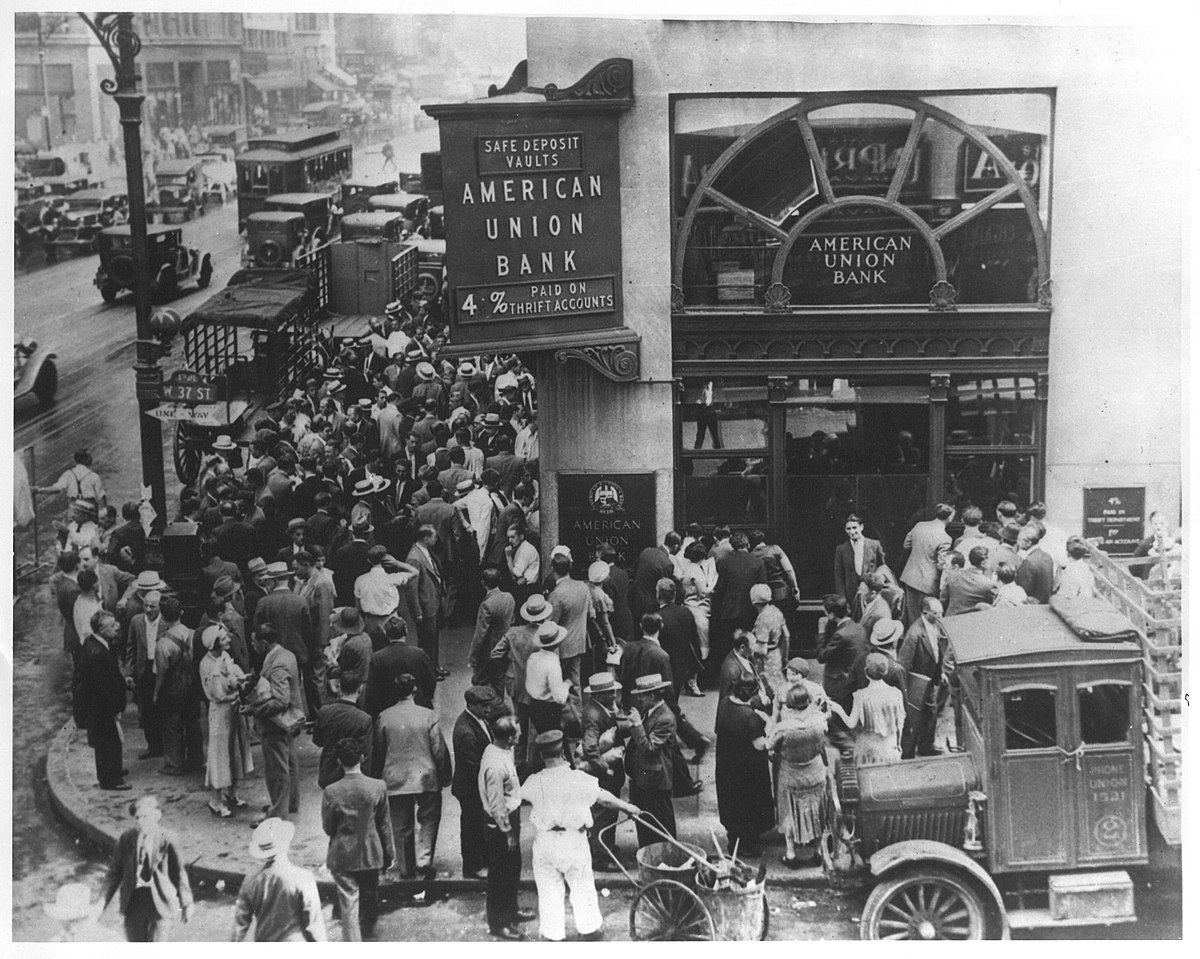

The good news is that with modern technology there’s no such thing as a run on the bank, because the bank doesn’t spend your money, it vaporizes it.

We were proud to be early adopters, back in the day. For example, I was the first editor at the enormous publishing company where I worked to own a personal computer — an Osborne with a four-inch screen and a storage capacity of a massive 64k worth of text, as I recall. I was among the first in my family to own a smartphone, and delighted in its capabilities. When it came to online banking, depositing checks with my phone, paying bills automatically and electronically, I was way out in the vanguard, and happily so.

I have always been a terrible typist, who with my manual typewriter often ruined an excruciatingly picked-out page with a misplaced digit on the last line, one who used gallons of whiteout. A day. Not only did the computer eliminate the agony of the misdirected fingertip, it invited me to play with alternate words and phrases, to see without penalty how different constructions would look on the page, and these were gifts beyond price for a struggling wordsmith. The phone, too, delivered value way beyond its price, acting as my navigator, internet browser, e mailer, entertainer and oh, yeah, it could make phone calls.

I have written elsewhere about how updates have nearly ruined my computer and smartphone. But more than that, the spread of technology oncology (more aptly christened by the folks over at Naked Capitalism “the crapification of everything”) is strongly suggesting to me that, as habitual early adopters, it is time for us to do a 180, as the pilots say. Continue reading →